Before powerful GPUs and multi-core processors made it possible for machines to learn from data, AI was about coding a deterministic algorithm. Thе old and well-explored principles of graph trees, constraint propagation and search still find many applications today.

Constraint Propagation and Search

Artificial intelligence is all about designing computer systems able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. We already know computers can do some arithmetic tasks like multiplying large numbers much faster than any human will ever do. But what about non-arithmetic tasks? Well, by now everyone knows that Tesla, Google, Apple and many other tech companies are working on autonomous driving. And yet, they haven’t completely cracked it yet. On the other side, it is now 20 years since IBM’s Deep Blue won both a chess game and a chess match against Garry Kasparov - the reigning world champion at the time. To sum it up - driving a car is obviously an easy task for humans, two billion people are driving to work every day, but it is very hard for a computer system to manage. At the same time, computer systems can beat the world champion at chess - a task that hardly any human can achieve. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

Coding a Sudoku Environment

Another non-arithmetic and seemingly human task at which computers excel is solving a sudoku. The use of constraint propagation and search is illustrated in this great blog post by Peter Norvig. In this post I will go one step further by introducing a small, but powerful optimization for Norvig’s solution. My whole sudoku solver implementation can be found in this repo: AIND-Sudoku.

In a sudoku, the rows, columns and 3x3 squares all contain digits from 1 to 9 exactly once. Norvig introduces a very flexible design, which is easily extended to a diagonal sudoku. Indeed, Norvig’s solution can be extended to solve a diagonal sudoku by just adding the diagonals to the units, used in the constraint propagation steps:

MODE_NO_DIAGONAL = 1

MODE_WITH_DIAGONAL = 2

DIGITS = '123456789'

ROWS = 'ABCDEFGHI'

COLS = '123456789'

def cross(A, B):

"Cross product of elements in A and elements in B."

return [a + b for a in A for b in B]

BOXES = cross(ROWS, COLS)

ROW_UNITS = [cross(r, COLS) for r in ROWS]

COLUMN_UNITS = [cross(ROWS, c) for c in COLS]

SQUARE_UNITS = [cross(rs, cs) for rs in ('ABC', 'DEF', 'GHI') for cs in ('123', '456', '789')]

DIAGONAL_UNITS = [[row+col for (row,col) in zip(ROWS, COLS[::step])] for step in [-1,1]]

def get_units_peers(mode):

if mode == MODE_NO_DIAGONAL:

unitlist = ROW_UNITS + COLUMN_UNITS + SQUARE_UNITS

elif mode == MODE_WITH_DIAGONAL:

unitlist = ROW_UNITS + COLUMN_UNITS + SQUARE_UNITS + DIAGONAL_UNITS

else:

raise Exception('Unknown mode.')

units = dict((s, [u for u in unitlist if s in u]) for s in BOXES)

peers = dict((s, set(sum(units[s], [])) - set([s])) for s in BOXES)

return unitlist, units, peersNaked twins strategy

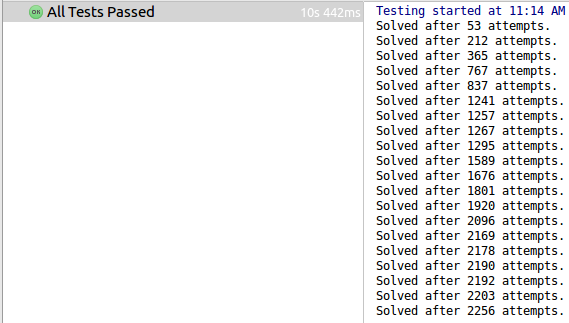

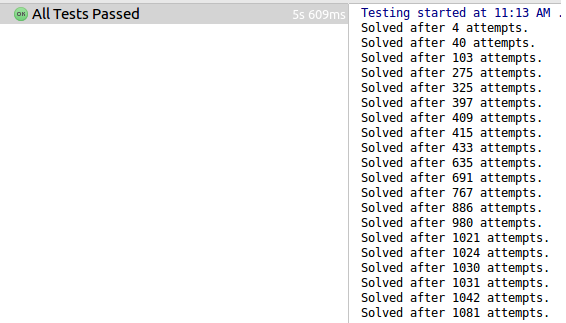

In solution_performance_test.py I added a small performance test to measure the time needed to solve 20 hard sudoku puzzles. I furthermore modified the code to print the amount of search attempts the solver needs for solving each sudoku puzzle. A search attempt is made whenever the potential of constraint propagation is exhausted and the algorithm has to try different digits for the same box. When executed the test output looks like this:

As previously mentioned, in order to solve a sudoku puzzle one needs to use only constraint propagation and search. To increase the performance of Norvig’s solution I simply added an additional constraint, called naked twins:

def naked_twins(values):

"""Eliminate values using the naked twins strategy.

Args:

values(dict): a dictionary of the form {'box_name': '123456789', ...}

Returns:

the values dictionary with the naked twins eliminated from peers.

"""

# Find all instances of naked twins

# Eliminate the naked twins as possibilities for their peers

for unit in UNITLIST:

unsolved = [box for box in unit if len(values[box]) > 1]

# indices of all pairs (0, 1), (0, 2), (0, 3), (0, 4),

pairs = list(itertools.combinations(unsolved, 2))

for i,j in pairs:

chars1, chars2 = values[i], values[j] # the characters in each pair

# if characters match, i.e. chars1 = '34' and chars2 = '34' they are twins

if len(chars1) == 2 and chars1 == chars2:

# all boxes that are not the twins

not_twins = [box for box in unsolved if values[box] != chars1]

for box in not_twins:

for char in chars1:

# remove the characters of the twins for each box that is not one of the twins

val = values[box].replace(char, '')

values = assign_value(values, box, val)

return valuesPutting it all together

Adding just this single constraint led to the significant performance boost. The time needed to solve twenty sudoku puzzles was cut in half. You can clearly see the algorithm is making far fewer attempts than before:

One can even go further and implement additional constraints. In the sudoku world those constraints are called sudoku strategies. So how good is a computer at solving a sudoku? In this Telegraph article I found a sudoku puzzle which was designed by Japanese scientists to be especially hard to solve. It is supposed to take hours if not days to solve. Below is a slow motion video of the algorithm solving the sudoku. Note, the video would be much longer if not for the naked twins strategy that is significantly reducing the number of unsuccessful attempts.

As you can see on the video, the algorithm is making quite a few unsuccessful attempts and consequent steps back. One thing is sure - an AI engineer will be faster at writing the code that solves a sudoku than actually solving a puzzle that hard.